The History of the Defenders’ Database

In 2009 and 2010, Hablemos Press (CIHPress) and the Cuban Commission of Human Rights and National Reconciliation (CCDHRN) started publishing monthly reports on human rights violations committed by the Cuban state. Their main focus was on arbitrary detentions, repudiation acts, political prisoners, beatings, and harassment. Both organisations built large national networks of reporters interviewing victims and witnesses, and took notes. The notes were called into the headquarters in Havana and compiled in reports.

As the democracy movement grew, the number of violations increased continuously. At the same time, the capacity of the organisations to record the data improved and, on various occasions between 2014 and 2015, both organisations recorded more than a thousand arbitrary detentions per month. The workload to analyse the data grew unbearable when the table in the PDF-reports from CCDHRN covered more than 30 pages, and the word-list of Hablemos Press stretched over 250.

Although a lot of effort went into the reports, the only figure that was highlighted in the news when they were published was the total number of arbitrary arrests. But there was so much more important information in the reports that was not possible to analyse or visualise as the report formats did not permit it. It was impossible to break down the data and analyse it in detail.

When discussing the issue with CCDHRN and Hablemos press, we realised that what they needed was an easy-to-use database to record and analyse the data (see the step-by-step feature) but also a parser that could read their old reports and import the information into the database. We could not permit that all their impressive work would be lost.

During 2016 and 2017 we built the different features of DiDi and imported all the monthly reports from Hablemos Press and CCDHRN from 2009 until today onto the database.

We also wanted to make it possible for journalists, diplomats, human rights organisations and anybody else to have access to the data, and the possibility to make their own analysis (See the map-and-graph tool).

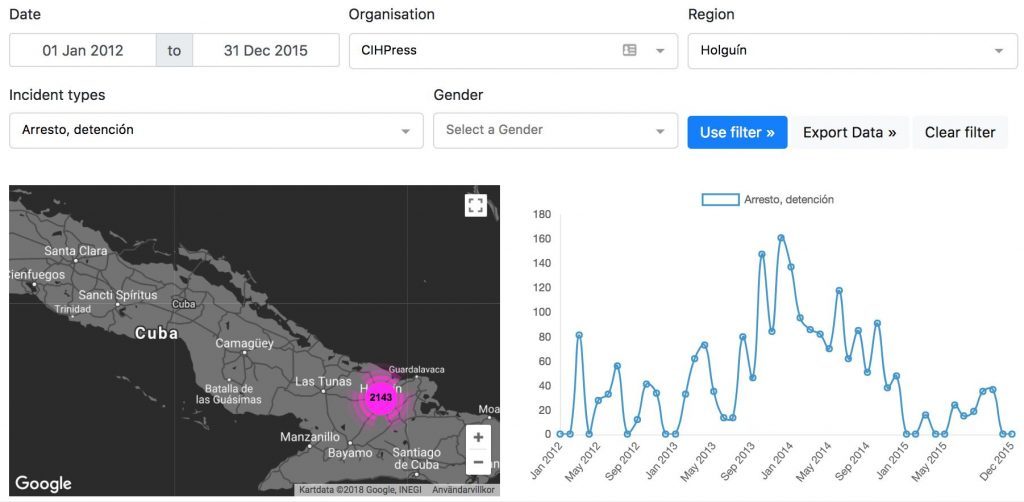

It has now become possible to connect the number of human rights violations in Cuba to the political development in the country. Before, Hablemos Press could neither show nor explain the spike in arrests in Holguin, in eastern Cuba, during 2013 and 2014, nor why it declined.

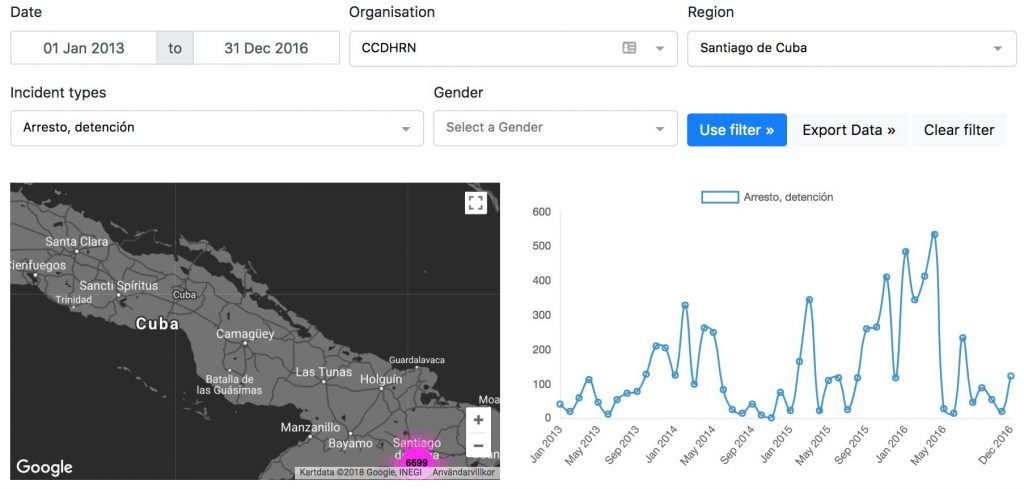

Furthermore, CCDHRN could not visualise the rise of arrests of protesters in Santiago de Cuba after the announcement in December 2014 by Barack Obama and Raúl Castro that they would normalise the diplomatic relations between the countries.

With the map-and-graph tool it is now possible to see these local trends and analyse and explain them.

In addition, the Defenders’ Database gives us an early warning system. Was the rapid decline in the number of arbitrary arrests recorded by CCDHRN in Matanzas in early 2015 the result of a major crackdown on the democracy movement? Or was it the consequence of one or more of CCDHRN’s reporters leaving the organisation, maybe even the country?

Had we seen this drop then, Civil Rights Defenders could have acted and called on other international partners to do the same. Thanks to DiDi, we will from now on be able to see development in real-time and act accordingly. DiDi has now given Hablemos Press and CCDHRN an opportunity to create completely new statistics and draw new conclusions from their data.

After 2015, the data from Hablemos Press is limited. The Cuban government launched a wide attack against organisations in the democracy movement at this time and succeeded in driving several of them into exile. Hablemos Press was one of the organisations that was targeted and most of their journalists and activists left the country or withdrew from the work. However, since 2017 they have started rebuilding the network and, thanks to the Defenders’ Database, they have been able to initiate their reporting again.